Allow me to be a pale imitator of Susan Douglas’

Where the Girls Are: Growing Up Female with the Mass Media. If you don’t own this book, buy it. It is too funny to put down. While you are at, pick up Vito Russo’s

The Celluloid Closet. It is old, but worth reading as well.

Douglas discusses the media’s relationship with women viewers. In the same spirit, I want to think about the ways that the media also plays a coy game with gay men. Many times, gay men become the fun joke or the “adult-theme” that adds zest to their shows, magazines, or films.

Most of these images deserve condemnation as homophobic. Soon-to-be-Ex, for instance, rightly gets outraged at these representations and writes about them in his blog (see his post on "Brokeback Mountain," for instance). Most times I agreed with him.

Where I split with him and others, though, is that I also think popular culture offers means of resistance. As much as the mainstream media derided (and continues to deride) gay men and women, it also created (and creates) opportunities to claim queerness through these same images. We have collectively interacted with the media, both accepting and rebelling against their assumptions about our sexuality.

It is too simple to limit our understanding about our queer past to iconic civil-rights leaders or events. Obviously, I am not at all minimizing these leaders. Believe me, I spend many of my classroom lectures informing my students about Bayard Rustin, Alan Ginsberg, Stonewall, Gloria Anzaldua, Harvey Milk, among others. It would be impossible for me to claim my queerness or enjoy my rights in this country (such that they are) without them.

Yet, I am willing to gamble that most queer folk don’t know about many of these leaders. Many of us learn about these figures

after we have already come out (sometimes decades later). Instead, it is through popular media, I believe, that many (most?) gay men and lesbians ultimately claim their identity in the United States. Unlike queer civil-rights leaders, almost everyone could identify the list of characters below. Probably the media was one of the first places that we all learned about “men like

that” or “

those women.” We, therefore, have much invested in media representations. Simply condemning these images ignores the many queer folk who also find validation in them.

Certain television shows come to mind. These offered some of the most prolific queer images, and many of them continue to live on through endless cycles of re-runs. These visions of queer men sent contradictory messages. Often these characters had the most popularity of their shows. Because they broke with gender expectations, they had much more fun than their hetero counterparts. Straight male characters faced lives of responsible drudgery working in stale offices. Straight women characters faired little better. Their days seem to center on pondering new ways to clean fingerprints off windows.

Queer characters, however, appeared above these hopelessly boring activities. In many ways, they seemed to offer an antidote to the tedium of suburbia. They also usually arrived with the best jokes, always made at the expense of straight-folk.

Still, these characters traded in stereotypes and appeared clownish. Almost all of the images that could be read as queer were white and middle class. As such, they served as a warning about failures to conform to those racial, gender, and class expectations. Their fun always came to an end. Queer characters appeared as threats to the domestic ideals of straight-white families. Always coming from outside of these happy homes, their time in the domestic sphere usually resulted in unsettling an otherwise happy family. While they may have laughed for twenty minutes, queer men ultimately faced banishment in the last two minutes of these shows. They almost always appeared alone and divorced from sexual activity.

Uncle Arthur

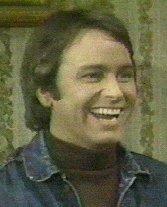

Before Paul Lynde became the iconic “Center Square,” he captured the nation’s attention in

Bewitched. Samantha always welcomed visits from her fun uncle, at least initially. Spending your days avoiding Mrs. Kravitz and mindlessly mixing cocktails for Darrin would prompt you to welcome Arthur’s quirky humor as well.

On the one hand, Arthur made no apologies and offered no explanations for being single. He delighted in his catty bitchiness. Arthur thumbed his nose (literally) at Darrin’s gender conformity, refusing to take on the conventional guises of masculinity. With his magic-driven practical jokes, he broke the stifling dullness of Samantha’s suburban prison. Arthur also appeared unique as the only one in the Bewitched world who never feared Endora (a lesbian icon waiting to be unpacked).

On the other hand, any explicit queer desires that Arthur may have had went unnamed in the show. The queerness that he did manifest was only permissible because of his association with Samantha’s secret magical world. Like most of her relatives, Arthur could not function, and was not welcome, in the day-to-day

hetero mortal world. Arthur’s exaggerated theatrics inevitably became a nuisance to Samantha, his only consistent friend on the show.

We, the audience, weren’t suppose to identify with Arthur. Rather, his bitchiness and refusal to adapt to suburbia ultimately isolated him from other people on the show. In the end, he always returned to the magic world alone.

Lost in Space’s Dr. Smith

Smith existed as an unhappy and unwanted addition to the ultra-perfect space-family Robinson. Seemingly he was as smart, or maybe smarter, than the Robinsons. He worked as a medical doctor for NASA, but he kinda forgot his medical training as the show progressed. He also was the only one besides the ever-eager Will who could repair the robot (most times he repaired it as an instrument to try to murder the aforementioned Will). Like Arthur, he offered one-line bitchy zingers to the hapless heteros who surrounded him.

Though a popular character, Smith portrayed the worst stereotypes for someone who bent gender expectations. In the first episode he took a bribe from some unknown traitor to murder the Robinsons. Throughout the rest of the show, he continuously brought chaos and destruction to the real heroes of the show: the happy, white, suburban family. He screeched and screamed whenever the robot warned “danger-danger.” Time and again, his lack of proper masculinity imperialed everyone around him.

Cowardly and shrill, Smith served as a warning to young queers about being too flamboyant. If one didn’t settle down, even your best friends would hate you (or maybe even die!). Smith, who had the sex appeal of a pencil eraser, affirmed that queers were often fools and really needed a stronger, heterosexual man to save them in the end.

Jack Tripper Three’s Company

Three’s Company offered a character who explicitly identified as gay, at least part of the time. True, he wasn’t

really gay. Instead, he only claimed to be gay so that he could live in a hot apartment.

For those who are under the age of thirty and/or don’t have cable, the premise of the show revolved around a straight, single man living with two straight, single women. The landlord of the apartment building (first Mr. Roper, later Mr. Furley) didn’t want any “hanky-panky” (his words, not mine) in his building and, thus, would have forbidden Jack from living there if he knew the truth.

Clearly the show traded on homophobia for cheap laughs. Whenever the landlord appeared, Jack began to swish and mince around the apartment, batting his eyelashes at the dim-witted landlord. These were the ways he pretended to be gay.

Still, Jack didn’t usually see claiming gayness as threatening to his own sense of masculinity. Despite his harsh and explicit homophobia, Mr. Roper/Furley accepted Jack as part of the family. Oddly, he even preferred to have a gay man living in his apartment building than a straight man. Jack Tripper’s character also opened the opportunity for me to ask my sisters (my source for all worldly information until I was 12) what it meant for someone to be “gay.”

Will and Grace Jack

Does anyone even watch

Will and Grace anymore? I haven’t seen an episode in five or six years.

Regardless, for the first time network television offered a long-lasting show about openly gay characters. Unlike their queer predecessors, who mostly appeared as guest stars, Will and Jack had a guarantee to return week after week.

Taking their inspiration from

The Object of My Affection, the show centered around the relationship between a straight woman and her gay best friend. Will and Grace made queerness safe by asserting a heternoramtive model of domesticity. Beyond the sex (and I think they might even had sex at some point), they looked like every other hetero couple on television.

We already know my feelings about Sean Hayes (click

here to read that diatribe). His character Jack, though, is a recycled version of Uncle Arthur. Just like Arthur, Jack brings chaos to the happy domestic world of Will and Grace. Jack lacks a job, lives alone, and is the constant joke of the show. Like Smith, he is often cowardly and shirks any real responsibility.

Together, Jack and Will make an uncomfortable gay couple, with Grace as an unwieldy third. The show tells us that gay people exist, but that being a gay man does not involve dating other men. Rather, being gay seems to be about fluttering around apartments and drinking.

Queer Eye for the Straight Guy

Much virtual-ink has already been spilled over the queer-eye guys. Still, they became such a media sensation it is hard not to comment on them.

Rather than the isolated sadness of Uncle Arthur or Dr. Smith, for a change we got to see five gay men who worked together and seemed to have fun. They still acted in a bitchy manner, but they also showed that they cared about each other. Each had talents that went beyond one-line zingers and practical jokes (except maybe Jai, who seemed fairly useless).

Each episode could easily be interchanged with another. Some hetero guy, who apparently can’t figure out how to work a toaster (probably because Mommy always did that for him), calls for queer help to set him straight(er). The queer-eye men appear at his door, instantly bond with him, and serve as his gay mammies. They take him shopping, show him how to order food from a caterer, and give him lots of free stuff for his house. Countless episodes culminate when the queer guys help the dumb-bell het propose to his hapless girlfriend (as if she could say “no” with an army of cameras zooming in on her face). All the time, the queer-eye guys never mention that they lack the same rights to marry their loved ones. Instead, we are treated to close-up shots of the queer eye guys getting teary-eyed as the proposal unfolds before them.

The queer-eye world contends that there isn’t an oppressive and homophobic nation that keeps many gay people in fear. Instead, queer men in the show are consumed by solving superficial problems (how to get a straight-guy to wash his face, for instance).

Though they express genuine fraternal affection with each other, nothing is ever said about their individual romantic lives. Like Will and Jack, for these men being gay is about everything

except having sex with other men.

After twenty something years with televison, I hoped that they would offer more rounded versions of gay folk. Television executives, instead, offer us a bad compromise. We have a few more images of gay men, and they actually get to identify as gay. They exist, though, in a never-never land that we could never mistake for own reality.

Yet, these images also provide contradictory opportunities for us to identify with them. This helps explain why many queer men are quick to defend things like "Brokeback Mountain." Rather than simply dismissing them as trivial, we need to consider our own complicated relationship with these visions of queerness. These images simultaneously provide a form of validation even as they lock queer folk into perpetual stereotypes.