Antonio Banderas’ impending sequel reminds me of my complicated relationship with Zorro. “What?” you ask, “GayProf has a complicated relationship with a mainstream-media icon? How unusual.” Yeah, yeah, I know. I am nothing if not predictable.

Still, blogging on Zorro is better than, say, dealing with my breakup (Does it show that avoidance is one of my coping strategies?). It is also better than writing the two encyclopedia articles that are now three weeks overdue.

It is not so much the new Zorro film that interests me. After all, Banderas hasn’t held my attention since he stopped working on Almodóvar movies. Rather, it is the interesting ways that the character Zorro crosses two intersections of my identity: queer and Latino.

When I was growing up, there were very, very, very, very, very, very, very, very, very, very, very, very, very, very few Latino characters in the mainstream media. Connect that with my life-long love of flowing capes, and you have an explanation for Zorro being my second-grade Halloween costume. I would provide a picture, but given I was the third child, my parents had pretty much lost interest in keeping a photographic record of their family by the time I was in the second grade. It's just another thing to add to my therapy sessions.

Annnnnnnyway, GayProf must stay focused. So – Zorro -- right.

Zorro’s many incarnations provide rare opportunities for us to see a Latino hero. Zorro contrasted the stereotypical Latino images that plagued U.S. visual culture. He was smart, handsome, charming, and committed to fighting social injustice. For those who don’t know Zorro’s original story (basically ignored by the Banderas’ movies), Diego de la Vega turned to vigilantism when Spain’s imperial authority over Alta California became corrupt. During the day, he lived out his role as the lazy son of a wealthy land-owner. Whenever the bumbling Sargent Garcia wrongly arrested somebody, though, Diego dashed off to the cave below his house. He put on a black costume, cape, cowl, and a small brimmed hat. With this outfit, he suddenly became invincible. He could burst apart corruption and help the weak, only stopping to carve Z’s into his enemies’ underpants.

In many ways, Zorro inspired the subsequent generations of superheroes who emerged in comic book form. Zorro, created in 1919, predated Superman, Green Lantern, and others by at least twenty years. Bob Kane, the creator of Batman, found more than a little inspiration from Zorro. Both characters, after all, are wealthy bachelors who, after going to their secret cave, play dress-up in long flowing capes. Indeed, Kane had young Bruce Wayne and his parents watching The Mask of Zorro before their untimely demise. All of this suggests Zorro’s strengths as a Latino icon.

Yet, Zorro’s story is not that simple. In contrast to many people’s assumptions, a Latino did not invent Zorro. His actual creator, Johnston McCulley, participated in the existing racial and national discourse from his time. Creating his hero for a popular pulp magazine, McCulley made Zorro an exception to the otherwise blood-thirsty and corrupt Latinos who surrounded him. Moreover, Diego de la Vega existed as a “racially pure” Spaniard in his first incarnation. The mixed-race and indigenous people who surrounded him appeared incompetent or in need of his rescue.

McCulley allegedly based Zorro on Joaquín Murrieta, a real-life California folk hero. Murrieta, however, fought gold-hungry Euro-Americans who threatened and harassed the existing Mexican population in the 1850s. McCulley apparently did not like this element of the story, probably because it exposed the negative elements of U.S. westward expansion.

McCulley made his version of Murrieta safe for Euro Americans by turning back the clock. Because Zorro’s stories took place before the arrival of Euro Americans in California, he never drew attention to the injustices that Latinos faced in the U.S. If anything, his adventures justified the U.S. invasion by showing most Latinos as incapable of self-government. Zorro’s archenemies, particularly the corrupt alcalde and incompetent Sargent Garcia, served as excuses for Manifest Destiny a hundred years later.

Zorro’s relationship to Latinos, though, is not the only element that intrigues me about this character. Zorro also has a peculiarly queer history. In many of his appearances, Zorro showed some sexuality-bending tendencies, the aforementioned flowing cape not being the least of which (Seriously, when are capes ever going to come back into fashion for men?). One has to wonder, for instance, just why did he always stop to cut off other men’s trousers? What are we to make of his carving his initial in their underpants? Was he marking his territory? And we won’t even begin to explore his love of the whip.

During the day-light hours, Zorro’s alter-ego, Don Diego de la Vega, spent time lounging about, often in a fey manner. Supporting characters in the 1940 Tyrone Power version probably came the closest to calling Diego a big-flaming queen, but hints existed through most of his many incarnations. Power, incidently, had a reputation for being a man-loving-man himself.

Then there was Guy Williams’ basket in the Disney televison show. I hate to go to the gutter, but take a new look at this old show. Diego’s costumes showed that Williams was packing. His matador trousers, I am sure, helped many queer boys discover their real interests. No wonder he had such following! But, I digress. . .

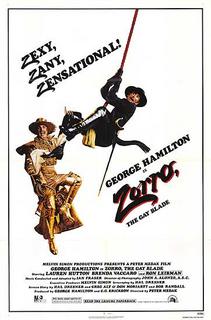

Though Zorro wooed women, Diego de la Vega spent most of his time dressing and undressing with his faithful servant, Bernardo. The early eighties even took this character divide to its logical extreme with the parody Zorro: The Gay Blade. In this version, the Diego character split into two twin brothers (Freud calling on line one). One brother, straight, becomes injured and can’t continue as Zorro. The other brother, gay and named Bunny, becomes an outrageous Zorro figure. Losing the traditional black costume, Bunny adds a splash of color. Still, he appears as competent as his straight brother in fighting injustice.

My love-hate relationship with Zorro, as you might deduce, is based on all of these conflicting elements. Oh, who am I kidding? I just want to wear that cape . . .

3 comments:

Conveniently, Halloween is just a few days away! Just make sure you post photos of yourself in the cape.

Hmmm. . . It is a hard choice between the cape or the bustier with the gold eagle and knee-high red boots.

Ah, Zorro.

The combination of Zorro, Tarzan and the Lone Ranger on Saturday afternoon TV when I was a child certainly caused all sorts of pleasently uncomfortable feelings.

Post a Comment